The following is my translation of a sub-section of the “Evils of the Tongue” taken from the Ihyā’ ‘Ulūm al-Dīn of Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī (d. 1111). Since I had recently translated and shared a text from another Sunni scholar (https://ballandalus.wordpress.com/2014/09/02/sibt-ibn-al-jawzi-d-1256-on-yazid-ibn-muawiya-d-683/) dealing with a similar issue (Yazid b. Mu’awiya and the permissibility of cursing him), I thought it would be useful to provide another perspective from another medieval scholar who, unlike Sibt b. al-Jawzi (d. 1256), declared that it is absolutely impermissible to invoke curses upon Yazid b. Mu’awiyah, whom he–in contrast to the vast majority of Sunni theologians and historians–exonerates of all responsibility for the massacre at Karbala. It is interesting that al-Ghazālī’s only commentary on a such a critically-important historical issue such as Karbala and the massacre of the Family of the Prophet Muhammad can be found embedded in an ethico-legal discussion on cursing. Although we are also in possession of a legal responsa (fatwa) by al-Ghazālī that is preserved in the Wafiyāt al-A’yān wa Anbā’ Abnā’ al-Zamān of Abū al-‘Abbās b. Khallikān (d. 1282) that provides a more explicit perspective on Yazid (I am currently working on translating it, and will publish it soon), it seemed necessary to translate and post the fuller discussion of the issue of cursing in general as presented in the Ihyā’ ‘Ulūm al-Dīn in order to provide the context for understanding the logic and rationale that informs al-Ghazālī’s position on the issue. This can allow us to better appreciate and understand his perspective, regardless of whether or not we agree with him.

Several questions are inevitably raised by his strong stance against cursing, a concept enshrined both within the scriptural tradition and the broader culture of medieval Islam. Was he perhaps concerned with the dangers posed by a sectarian appropriation of cursing, given the central role of tabarru’ within Shi’i Islam? Perhaps, as a former government official, he also understood its subversive qualities and its capacity to be used as a tool of the oppressed against the central authorities? Is it even possible that he sought to preserve the integrity of the institution of the caliphate by seeking to disassociate Yazid b. Mu’awiya from the massacre of the Ahl al-Bayt at Karbala? It is clear that a variety of considerations–ethical, legal, theological, social and political–played an important role in determining al-Ghazālī’s position on the issue. The inclusion of the section on the status of Yazid, however, inclines the historian to believe that there is more at work in this section than a mere discussion of ethical behavior.

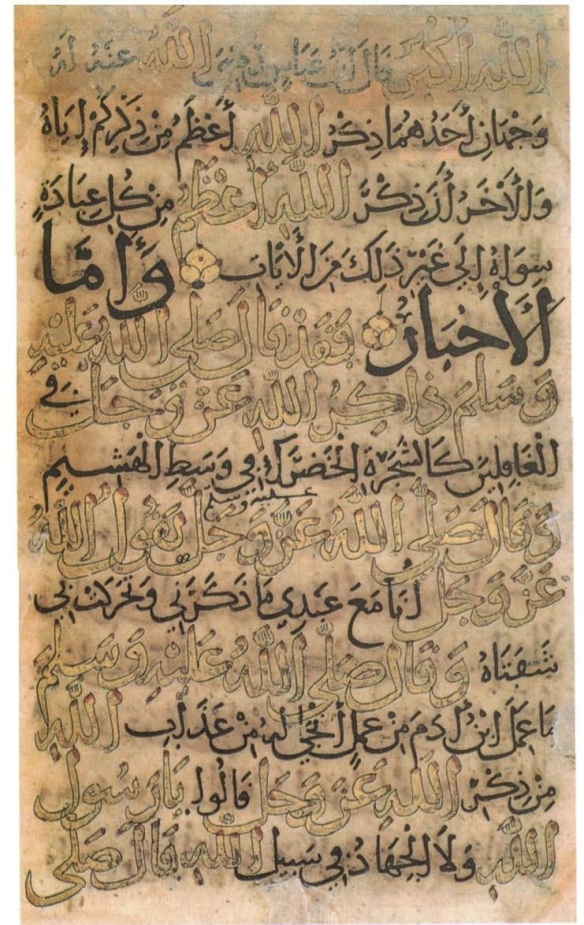

Translation

[Among the evils of the tongue] is cursing (la‘n). It is a reprehensible practice, whether deployed against an animal, an inanimate object, or another human being. The Prophet (may the peace and blessings of God be upon him) said: “Verily, the believer is not one who curses.” He also said: “Do not curse another with the curse of God, His Wrath, or His Hellfire.” According to Huẓayfa “Whenever an individual curses another, the curse will rebound upon themselves.” ‘Imrān b. Ḥuṣayn narrated that during one of the Prophet’s journeys, he was passed by a woman from among the Anṣār riding on a camel. The animal irritated her in some way so she cursed it. As a result the Prophet said: “Unload the camel and drive it away, for it has been cursed.” [‘Imrān] said: “After that, I saw the camel roaming among the people and none approached it.” Abū al-Dardā’ said: “No one has cursed the Earth except that it has replied ‘Accursed be the most sinful inhabitant among us.” ‘Ā’isha (may God be pleased with her) related: “The Prophet (may the peace and blessings of God be upon him) heard Abū Bakr while he was cursing one of his slaves, so he told him: “O Abū Bakr, I swear by the Lord of the Ka‘ba, that the characteristics of truthfulness and cursing can never be harmonized” and he repeated this twice or three times. On that day, Abū Bakr freed his slave and came to the Prophet (may the peace and blessings of God be upon him) and told him: “I will never curse anyone again” to which the Prophet (may the peace and blessings of God be upon him) said: “Verily, those who curse will not be intercessors nor witnesses on the Day of Resurrection.” Anas related: “A man was traveling with the Prophet on his mule, and then cursed his mule, so the Prophet (may the peace and blessings of God be upon him) rebuked him and said: ‘O ‘Abd Allāh, do not travel with us if your mule is indeed cursed.”

To curse means to drive away and distance something or someone from God Almighty. It is only permissible to curse things that are already distant from God, such as disbelief or oppression and to only do so with words that are permitted by the Shari‘a such as: “May the curse of God be upon the oppressors and the disbelievers!” since cursing is a grave matter indeed. Only God Almighty truly knows whether someone or something is accursed—since this is a matter of the Unseen—and the Prophet can only be given access to this knowledge [of who or what is cursed by God] if God Almighty permits him.

There are three requirements for cursing to be valid: 1) disbelief, 2) reprehensible innovation, and 3) sin. Cursing an individual/group belonging to each of these three categories is further subdivided into three classifications:

- Cursing in a very general sense, which is [generally] permitted. For example: “may the curse of God be upon the disbelievers, the innovators, and the sinners.”

- Cursing specific groups, such as invoking the curse of God upon the Jews, the Christians, the Zoroastrians, the Sabians, the heretics, the Kharijites, or the Shi‘ites, or—similarly—invoking the curse of God upon adulterers, oppressors, and those who deal in interest; all this is permissible. However, there is great danger in cursing the various sects of innovators because it is often obscure or difficult to recognize what constitutes a reprehensible innovation and, as such, the common folk should be restrained from cursing [anything they consider to constitute innovation] because this may lead to great corruption and civil strife among the people, who will begin to exchange curses between each other [with each accusing the other of innovation].

- Cursing a specific individual, which is impermissible. Examples of this include invoking curses upon an individual because he is accused of being a disbeliever, a sinner, or an innovator. The only exception to this is cursing the individual whose disbelief was clearly manifest, as in the case of invoking curses upon Pharaoh and Abū Jahl, since it has been firmly established that these individuals died while in a clear state of disbelief. However, with regard to cursing one of your own contemporaries by saying—for example—“may the curse of God be upon Zayd, for he is a Jew,” this is reprehensible and dangerous because there exists the possibility that this individual may one day convert to Islam and become beloved to God, so it would be illegitimate for him to be considered accursed.

And if it is said that he should be cursed due to the fact that he is a disbeliever, just as mercy is invoked upon a Muslim by virtue of the fact that he is a Muslim—even though it is possible that the latter may apostatize—it should be clarified what we mean when we invoke mercy upon someone. It basically is a request to God to strengthen this individual’s obedience to God and their adherence to Islam, which is the very cause for God’s mercy. It is unthinkable to request God to strengthen the disbeliever upon what is the very cause for cursing him, which is his disbelief. Rather, it is permissible to say: “May God curse him if he dies while persevering in a state of disbelief and may God not curse him if he dies while adhering to Islam.” In either case, the status of this person is ultimately unknowable since this is from among the Unseen things known only to God Almighty and, therefore, invoking curses upon this individual is unwise and even dangerous, while there is absolutely no danger in refraining from cursing him. Since this is principle true in the case of disbelievers, it is truer of fellow believers, whether they be sinners or innovators. There is great danger in explicitly cursing a specific individual, because the inner state of an individual is unknowable to everyone except God Almighty. The exception is only those individuals whom the Prophet [having given special knowledge from God] was certain would die while in a state of disbelief. It was because of this that he explicitly cursed several individuals by name, as is clear from his invocation against the Quraysh: “O Lord, curse Abū Jahl b. Hishām and ‘Utba b. Rabī‘a.” For an entire month, the Prophet would curse the disbelievers who killed his Companions during the Expedition of Bi‘r Ma‘una in his invocation during prayers (qunūt) , until God revealed the verse “It is not your decision; He may redeem them and be merciful towards them or He may punish them for their transgressions” [Q. 3:128], meaning that since there is the possibility that they may become Muslims, it would be wrong to assume that they are accursed.

It is permissible to curse an individual if it is certain that he died a disbeliever, although there are exceptions to this as in the story narrated in which the Prophet (may the peace and blessings of God be upon him) asked Abū Bakr (may God be pleased with him) about a tomb which they had passed on the road to Tā’if, and the latter said: “This is the tomb of a man who was insolently and violently opposed to God and His Prophet, here lies Sa‘īd b. al-‘Āṣ.” Upon hearing this, [Sa‘īd’s] son ‘Amr b. Sa‘īd was angered and said: “O Prophet of God, this is the tomb of a man who was more gracious to the needy and more beneficent to the poor than Abī Quhāfa [Abū Bakr’s father].” Abū Bakr then said: “O Prophet of God, it is outrageous that this man has addressed me with such vile words!” and the Prophet told ‘Amr: “Leave Abū Bakr alone.” When ‘Amr departed, the Prophet turned to Abū Bakr and said: “O Abū Bakr, when you mention the disbelievers, do not mention them by name because if you do so you may anger their children, due to the natural inclination of sons to defend their fathers,” and so the Prophet told people to avoid doing that [i.e. cursing disbelievers by name].

A certain Companion of the Prophet, Nu‘aymān, drank alcohol and was being whipped as punishment for his sin in the presence of the Prophet. Some of the Companions said to him: “May the curse of God be upon him!” to which the Prophet replied: “Do not be an aide to the Devil against your own brother,” or—according to another narration—“Do not curse him, for verily he loves God and His Prophet,” thus forbidding people from cursing him. This is proof that it is impermissible to explicitly and specifically curse a sinful Muslim by name, and—generally—there is great danger in cursing anyone explicitly, so this should be avoided. However, there is absolutely no danger in remaining silent and even refraining from cursing the Devil, let alone other human beings.

And if it is said “is it permissible to curse Yazīd because of his murder of al-Ḥusayn or ordering it?”, we respond: this fact is unverified and, as such, it is impermissible to even assert that Yazīd killed al-Husayn or ordered his murder since this is an unverified accusation. Thus cursing is certainly impermissible since it is not permitted to accuse a Muslim of a major sin [such as murder] without evidence. Verily, it is permitted to state that Ibn Muljam killed ‘Alī and Abū Lu’lu’ killed ‘Umar because that has been established by clear proofs and is narrated by multiple chains. It is absolutely impermissible to accuse another Muslim of sinfulness or disbelief without clear evidence.

The Prophet (may the peace and blessings of God be upon him) said: “Whenever someone falsely accuses another of disbelief or sinfulness, the accusation will rebound upon himself.” He (may the peace and blessings of God be upon him) also said: “Whenever an individual accuses another of being a disbeliever, then surely one of them is truly a disbeliever; if the accused is a disbeliever, then the accuser has spoken true, but if the accused is not a disbeliever then the accuser himself has become so by his anathematization of that individual.” This means that if an individual knowingly declares another Muslim to be a disbeliever, with the full knowledge that that individual is a believer, then he is a disbeliever. However, if he declares another Muslim to be a disbeliever as a result of some innovation that the accused has committed, then the accuser has merely erred, and is not a disbeliever. Mu ‘ādh [b. Jabal] related: “The Prophet of God (may the peace and blessings of God be upon him) said to me: ‘I forbid you from cursing a fellow Muslim or from disobeying a righteous ruler.” And slandering the honor of the dead is indeed far more grievous. Masrūq related: “I entered into the presence of ‘Ā’isha (may God be pleased with her) and she said: ‘What did so-and-so, may God curse him, do?’ I replied that he had died. She said: ‘May God have mercy upon him.’ I asked what she meant. She said: ‘The Prophet (may the peace and blessings of God be upon him) said: ‘Do not curse the dead, for verily they have reaped what they have sown.’ He (may the peace and blessings of God be upon him) also said: “Do not curse the dead in order to harm the living [i.e. their relatives].’ He (may the peace and blessings of God be upon him) also stated: ‘O people, preserve my memory by respecting my Companions, my brothers, and my kinfolk and do not curse them! O people, when a human being passes away, mention only their good deeds.’”

If it is said: “Is it permissible to say ‘may God curse the murderer of al-Ḥusayn’ or ‘may God curse the one who ordered the murder of al-Ḥusayn’?”, we say that it is correct to say ‘may God curse the murderer of al-Ḥusayn if he died before repenting,’ because there exists the possibility that the individual in question may have repented of his sinful action before his death. Indeed, Wahshī, the murderer of Ḥamza [b. ‘Abd al-Muṭṭalib] the uncle of the Prophet, murdered Ḥamza when he was still a disbeliever, but later repented from disbelief and his murderous act and thus it is not permissible to curse him. Even though murder constitutes a major sin, it is not disbelief so even if it was unproven that he sincerely repented from his act of murder, there would still be a major danger in cursing him. However, there is no danger in remaining silent and this should be the preferred course of action.

We have written this because unfortunately many people have belittled the gravity of the issue of cursing and have frequently uttered curses with their tongues, believing it to be a fleeting matter. I state again: the true believer is not one who curses and should only curse the one who died in a state of disbelief or ensure that they curse in a general sense without specifying individuals, and it should be remembered that it is best to occupy oneself with the remembrance of God and, if not, silence is the safest course of action. Makkī b. Ibrāhīm said: “I was with Ibn ‘Awn when Bilāl b. Abī Burda was mentioned. The people present then began to invoke curses upon him and disparage him, while Ibn ‘Awn sat there quietly. The people said: ‘O Ibn ‘Awn, we are cursing him as a result of the evil that he has done to you!’ Ibn ‘Awn replied: Two phrases will emerge from the book of deeds on the Day of Resurrection: ‘There is no God but God Alone’ and ‘may God curse so-and-so,’ and I would prefer that only the first phrase and not the second one is recorded on my behalf.” Once, a man said to the Prophet (may the peace and blessings of God be upon him): “Give me advice!” The Prophet told him: “I advise you not to curse anyone or anything.” Ibn ‘Umar related that the most hateful of people in the sight of God is the one who curses and slanders others. Others also related that cursing a believer is like killing him. When he heard this hadith, Ḥammād b. Zayd asserted that even if there were deficiencies in its chain of narration, it should still be considered authentic [in meaning]. Abū Qatāda related, in a hadith with a marfū‘ chain of narration, that the Prophet (may the peace and blessings of God be upon him) said: “Whoever curses a believer, it is as if he has murdered him.”

Another practice that is similar to cursing is praying that evil befalls an individual and invocations that evil befall tyrants. Saying “may God take away his health” or “may God weaken his body” is as equally deplorable and reprehensible as cursing.

[Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī, Ihyā’ ‘Ulūm al-Dīn (Damascus: Dar al-Fiha’, 2010), Vol. 4, pp. 91–98]

Ayatullah Naraqi in his invaluable work Jami’ al-Sadaat also speaks about cursing and states that it is – generally speaking – impermissible. However, he goes into some detail with regards to its exceptions.

A rough translation of it can be read here: http://www.iqraonline.net/hitting-swearing-cursing-and-taunting/