The Tibyan, which was written in Arabic by ‘Abd Allah bin Buluggin, the last Zirid emir of Granada (r. 1073-1090) sometime around 1094, is among the best sources for the end of the Taifa period, an era of division and fragmentation following the collapse of the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba. The text describes the division of Muslims in Spain into two hostile groups, Andalusis and Berbers, and provides crucial insight into issues such as as the advance of the Christian kingdoms, the political intrigues between Muslim and Christian rulers and the growth of the city of Granada as a new Muslim capital and political force in the Iberian peninsula. The work also provides important eyewitness accounts of battles and sieges and contains many colloquial Andalusi expressions which demonstrate the vernacular Arabic of the period.

One of the most interesting elements of the work is its constantly distinguishing between two groups, the indigenous Andalusi Muslims and the newly-arrived Berbers. The latter are always seen as in an inevitable state of conflict with the former and Abd Allah ibn Buluggin continually points to the cultural (even “ethnic”) differences between the two. In doing so, the work undercuts the usefulness of the term “Moor” as an analytical category in scholarship of medieval Iberia by demonstrating that not only did the Muslim population of Spain consist of various groups and sub-divisions, these groups were themselves acutely aware of such differences. Surely, then, terms such as “Andalusi” or “Berber” (although the latter certainly carries with it problematic connotations), or simply “Muslim” would be good substitutes for the archaic, vague, and frankly quite racist term “Moor”.

The Tibyan is also of major importance for the scholar of medieval Iberia because it sheds important light on the nature of Muslim civilization in Iberia between the fall of the Umayyad Caliphate in 1013 and the Almoravid conquest in 1091. The picture provided is one of ever-changing political realities and fluid alliances, where Christians allied with Muslims against other Muslim kingdoms and Muslim kingdoms allied with Christians against their other Christian rivals as well. There is nothing to indicate a religiously-inspired war between Islam and Christianity, let alone an all-out “Reconquista” on the part of the Christian kingdoms. The Tibyan also shows us the degree of cultural efflorescence in al-Andalus during the period, due largely to the rivalry between the various states. The work itself is a testament to the high-culture of the elites of Muslim Iberia during this period, with the author–himself a Berber–demonstrating his erudition in such fields as theology, philosophy, astrology in addition to history and poetry.

There are some important eye-witness accounts of various battles and sieges provided by Abdullah ibn Buluggin, which gives the historian of the period rare insight into the nature of warfare in al-Andalus during this period. The nature of statecraft is also given a considerable amount of attention by the emir, as he seeks to give some insight into the nature of polities, the best way to rule, and the most effective mechanisms of government. His dislike of overbearing viziers and secretaries is made evident by his continual use of the term tabarmaka (“to lord it over”) to describe their actions. This term, seemingly coined by the author, derives from the name of the Barmakid family, who served the early Abbasids as viziers.

One of the most important aspects of the work, however, is its representation of Granada. For the first time in Andalusi history, the city acquired prominence. In fact, it appears that prior to the arrival of the Zirids, Granada was merely a village which neighbored the town of Elvira. The population of the city, according to Abdullah ibn Buluggin, was predominantly Andalusi Muslims and Jews; in fact, the earliest name of the town was “Granada of the Jews” (Gharnatah al-Yahud). The Jewish community is discussed at some length. The Tibyan emphasizes their elevated role in both the political and fiscal administration of the city and explains that this occurred because the Jews–being unconnected to any broader interest in the Iberian Peninsula–were viewed as far more trustworthy than the Andalusi Muslims by the newly-arrived Zirids.

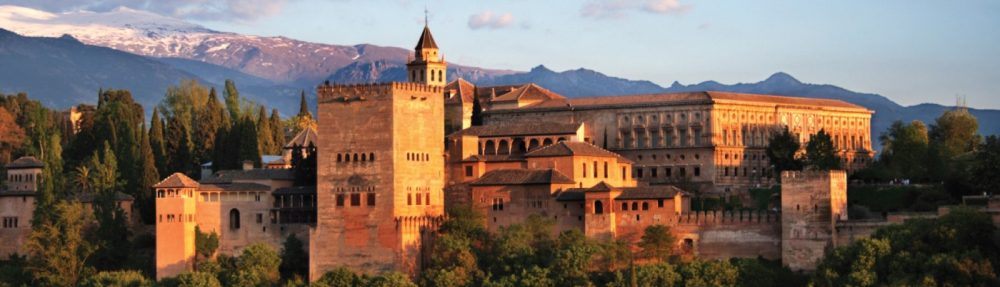

We are given some insight into the nature of the power wielded by Samuel ibn Naghrillah (Samuel haNagid) and his son, Joseph/Yusuf. While the former is described in illustrious terms as the “great vizier” and “shaykh Abu Ibrahim,” his son Joseph is described in very negative terms, probably as a result of his alleged involvement in the conspiracy which led to the death of Abdullah’s father. In any case, we are given a very interesting piece of information about Joseph ibn Naghrillah: “Out of fear of the [increasingly-hostile] populace, Yusuf moved from his house to the citadel (qasaba)…moreover, it is suspected that he had built for himself the Alhambra fortress (al-Hamra’) with a view to taking refuge there with his family…” This sentence, mentioned in passing, provides important evidence about the origins of the fortress-palace complex of the Alhambra, which would become the most prominent symbol of Granada in the Nasrid period. It seems, then, that the magnificent structure of the Alhambra owes its origins, at least in part, to Joseph ibn Naghrillah. Unfortunately for Joseph, the fortress was unable to protect him and he was assassinated in 1066. Even more tragically, a mob of Granadans massacred over 4000 members of the city’s Jewish community in the aftermath of the political crisis which culminated in Joseph’s murder. This was one of the most terrible and brutal massacres in the history of al-Andalus. The entire narrative, therefore, serves to highlight the tenuous position of the Jewish community in al-Andalus, which could be elevated to a position of power by one ruler, only to be massacred and subjected to oppressive violence during the reign of his successor.

Finally, the Tibyan sheds important light on the utter political and military weakness of the Taifa kingdoms in withstanding the expansion of the northern Christian states, especially during the reign of Alfonso VI. As such, it highlights the major impact that the Almoravid conquest had on al-Andalus and the necessity of their intervention in preventing the peninsula from being completely overwhelmed by the expansionist Kingdom of Castile. It explains the circumstances that led the Andalusi princes to appeal to the puritanical Almoravids and their unsuccessful attempts to maintain their independence from the latter. Abdullah ibn Buluggin’s Tibyan is also one of the only contemporary accounts of the Battle of Zallaqa/Sagrajas (1086) in which the Almoravids, led by Yusuf ibn Tashufin, defeated Alfonso VI. Since the author was a participant in this battle, the testimony is quite valuable. Given the rather rough treatment of the Taifa emirs–including Abdullah ibn Buluggin himself, exiled to Aghmat in southern Morocco–it is quite extraordinary that he was able to discuss the Almoravid conquest with relative impartiality.

Overall, the Tibyan is one of the most important texts that we have for the Taifa period and early Almoravid period in al-Andalus. The details that it provides about political institutions, communal relations, the dynamics of society, and even the role of women are quite important in affecting the way that we view this particular period of Andalusi history. It is a valuable read for scholars of both al-Andalus and the Islamic world in the medieval period.

The book has been translated into English by Amin T. Tibi as The Tibyan: Memoirs of Abd Allah b. Buluggin, Last Zirid Emir of Granada. Leiden: Brill, 1986.

Pingback: The Taifa Kingdoms (ca. 1010-1090): Ethnic and Political Tensions in al-Andalus during the 11th Century « Ballandalus