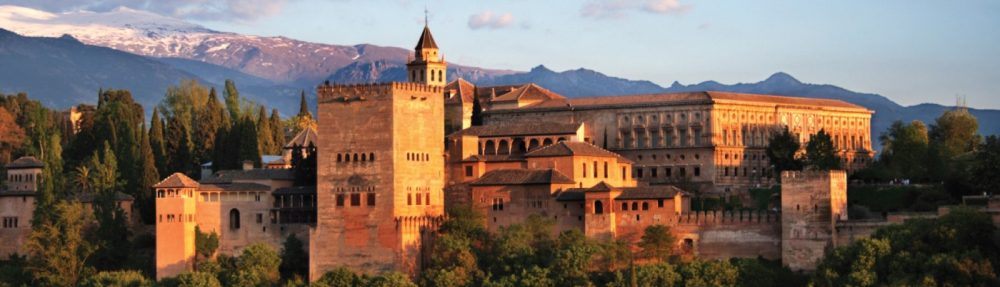

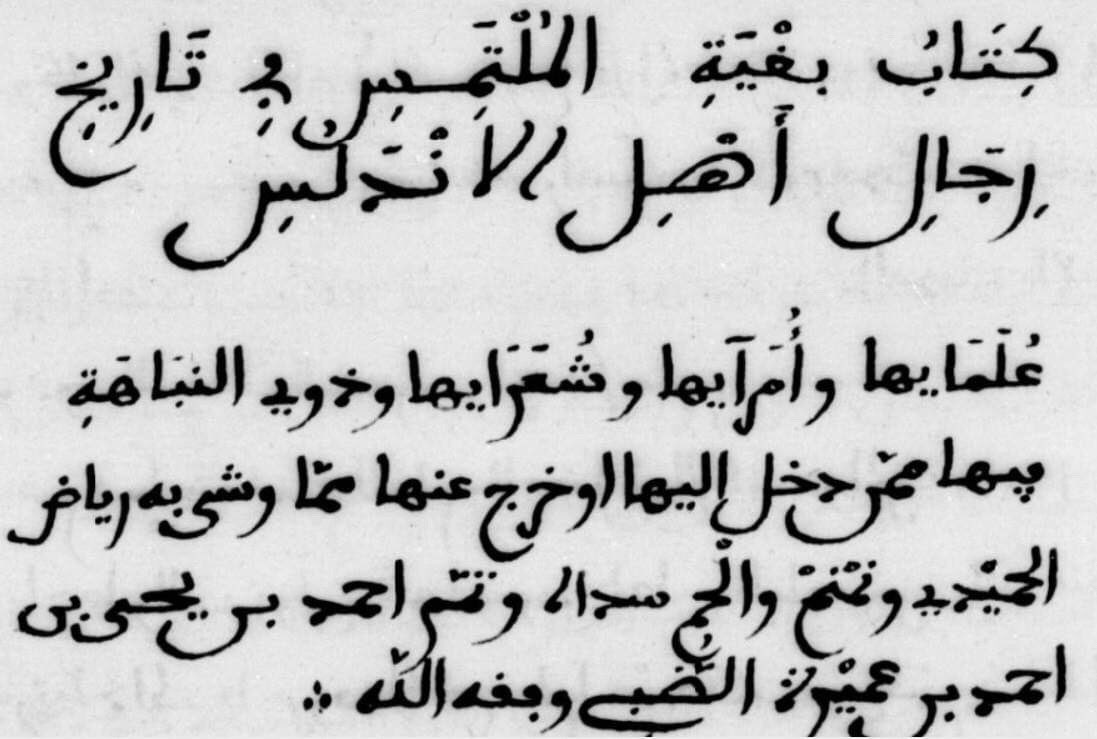

The following is a short translation of a short section of ‘Abd Allāh b. al-Sabbāḥ’s Nisbah al-Akhbār wa Taẓkirat al-Akhyār. Very little is known about the author apart from the fact that he was an Andalusī Muslim from Sharq al-Andalus, i.e the territory in eastern Iberia under the dominion of the Crown of Aragón. He was born at some point in the mid to late fourteenth century into a family of Mudéjars, a community of Muslims living under non-Muslim rule. At a young age, Ibn al-Sabbāḥ set out on his long journey to the East. His travels took him across Iberia to Nasrid Granada, Marinid Morocco, Hafsid Tunis, Mamluk Egypt, the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, Yemen, Syria, the Ottoman and Byzantine domains, as well as parts of Central Asia and Iran. He apparently returned to the Islamic West (although there remains a difference of opinion as to whether he returned to al-Andalus itself) early in the fifteenth century and wrote his travelogue shortly thereafter.

The text is unique because it provides historians with a detailed travel account by a 14th/15th-century Mudéjar from the Crown of Aragón and, thus, provides some insight into how an individual from this community perceived the various developments, institutions and personalities throughout the Islamic world. It also represents a perspective of the broader Islamic world by an Andalusī Muslim, who often sought to stress the relative military might of other Islamic dynasties vis-à-vis the Christian West in order to contrast it with the relative weakness of the dynasties in the Islamic West and the rather precarious position of Muslims in al-Andalus. Due to the nature of medieval travel accounts, it is of course impossible to verify with any certainty the specific details or claims made by Ibn al-Sabbāḥ in the text, but it nevertheless has important value in illuminating the worldview of a late medieval Mudéjar.

The section I have translated below deals with Ibn al-Sabbāḥ’s travels in Byzantine and Ottoman lands in the late fourteenth century, where (according to his account) he spent four years of his life. The reader will note how the text abounds with basic factual errors, myths and inaccuracies, underscoring the author’s lack of knowledge regarding the specific political history of that region. An illustrative example is his emphasis on the marriage alliance between the Kantakouzenos emperors and the Ottoman house. Ibn al-Sabbāḥ points out that the Byzantine Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos (r. 1347–1354) married his sister Theodora Kantakouzene (d. after 1381) to the Ottoman sultan Orhan (r. 1326–1362); in fact Theodora was John’s daughter (although the confusion may stem from the fact that her brother also became emperor shortly thereafter). Moreover, Ibn al-Sabbāḥ does not realize that Theodora was not the mother of Sultan Murad I (r. 1362–1389). Rather, the latter was the son of Nilüfer Hatun (d. 1383), the daughter of a prominent Byzantine commander but not related to the Kantakouzenos family . Ibn al-Sabbāḥ’s knowledge of Byzantine imperial history is also lacking as he erroneously claims that the current ruling dynasty was descended from Heraclius (r. 610–641). The same lack of knowledge underpins his strange claim that the Ottoman royal family was descended from the Abbasids, a statement perhaps derived from a local legend in one of the many lands that he visited throughout his travels. At times, he even makes basic mistakes about early Islamic history, wrongly placing the first Arab siege of Constantinople (674) during the reign of ‘Abd al-Malik b, Marwān.

As with many travel accounts, its usefulness to the historian is in its author’s specific interactions in the lands they visited. As such, the account about Ibn al-Sabbāḥ’s visit to the Hagia Sophia and his admiration for the relics and icon in that basilica demonstrate the genuine curiosity of this Andalusī traveler for the new lands that he visited. It is through this specific anecdote that the reader also discovers that Ibn al-Sabbāḥ was fluent in Catalan and (apparently) understood some Italian, thus giving us additional insight into interpersonal interactions in the Mediterranean world of the 14th and 15th centuries.

Continue reading →